MRPC 7.2(d)’s legal advertising rule puts an end to lawyers’ ability to advertise on Google and Facebook, violates First Amendment Free Speech rights

[UPDATE ON LAWYER ADVERTISING RULE: On March 27, 2019, the Michigan Supreme Court unanimously adopted a new ethics rule that applies to lawyer advertising. Generally, lawyer advertisements will be required to include the name and contact information of a lawyer responsible for the ad’s content. However, this requirement will not apply to many internet ads – such as paid-search ads on Google and ads on social media – where character and text-size limitations will make compliance impractical. In those advertisements, the rule requires that the lawyer’s name and contact information “be prominently displayed on the home page of the law firm’s website.” Significantly, this exception accommodates concerns that I raised in my blog post and in my letters to the justices which I submitted during the official comment period. The new lawyer advertising rule, which will appear as subsection (d) of Rule 7.2 of the Michigan Rules of Professional Conduct, takes effect on May 1, 2019.]

Carefully crafted rules of professional conduct for lawyers are essential in protecting the public. Unfortunately, some ethics rules don’t accomplish their intended goals. They do not protect the public and are, at best, unduly burdensome. At worst, they are completely unworkable.

Which brings me to the recent amendment to Rule 7.2 of the Michigan Rules of Professional Conduct.

This recent amendment does nothing to protect consumers of legal services, but as written it creates expensive and absurd outcomes for lawyers.

The rule’s disclosure requirements, coupled with the space limitations that currently exist, effectively put an end to how lawyers use the internet and social media to market legal services to consumers. The rule makes it impossible for lawyers to use Google and Facebook, for example, to engage in constitutionally protected commercial speech.

Despite laudable intentions, the unintended consequences make it now impossible for lawyers to participate in most forms of paid online advertising. We have a new ethics rule that is attempting to regulate 20th Century legal services like television, billboards, bus wraps and yellow pages in a 21st Century world.

What is the new legal advertising rule and disclosure requirements for attorneys?

On May 30, 2018, a unanimous Michigan Supreme Court adopted the following new legal advertising rule as an amendment to Rule 7.2 of the Michigan Rules of Professional Conduct:

“Services of a lawyer or law firm that are advertised under the heading of a phone number, web address, or trade name shall identify the name, office address, and business telephone number of at least one lawyer responsible for the content of the advertisement.”

The new rule takes effect on September 1, 2018.

Law firm signs, names, and trade names

Almost all of the biggest law firms in Michigan are named after deceased founding partners. Many other law firms use trade names – like “Michigan Immigration Lawyers” (a fictional example) or my own law firm, Michigan Auto Law.

Many of these law firms use prominent signs to identify their offices. Here are the signs of two of Michigan’s largest law firms:

To be sure, neither Jason L. Honigman (deceased) nor Raymond K. Dykema (deceased) are “responsible for the content of the advertisement.”

Because both of these gentlemen are dead, these law firms, and countless others, will have to change their signs to include the “name, office address, and business telephone number of at least one lawyer responsible for the content of the advertisement” under this new ethics rule.

Lawyers and clients will both be left to wonder:

- What’s the name of the law firm?

- Who is the person whose name appears beneath the deceased lawyers on the sign? Is she or he a lawyer? What is the connection between the two?

- Is this the same law firm I was looking for? Despite countless dollars spent on branding legal services, consumers will wonder if this is a different firm, or a firm that is masquerading on a similarly-named, but far more successful law firm?

Justice Bridget M. McCormack’s concurring statement in the Supreme Court’s January 10, 2018 administrative order asked whether a sign stating “1-800-LAW-FIRM” would require disclosures under Rule 7.2(d). The State Bar of Michigan answered Justice McCormack’s inquiry with an unequivocal “yes.” Although the Court didn’t incorporate the State Bar’s comment into the rule itself, Justice McCormack’s question and the Bar’s response suggests the rule means the vast majority of law firms will now be forced to have to change the signs on their office buildings.

I changed our own law firm’s name to Michigan Auto Law many years ago. It better reflects what we do as lawyers as an auto accident law firm. Since we never wanted to be one more personal injury law firm on TV, we arguably don’t have a “brand.” In fact, unless you are already a Michigan personal injury lawyer, you probably don’t know who I am by my last name because I don’t spend millions of dollars doing outbound/interruption based marketing like television and billboards. I write a blog, and I practice law helping people. I believe that for consumers of legal services who are looking for help after a serious car accident, these people are far better served. No one would know what I do if the law firm were named “law offices of Steven Gursten.” But everyone knows what we do because we practice under the trade name of “Michigan Auto Law.”

So with this new rule change, I’m imagining how the conversation will go with my wife and my children when I tell them that we will have to change our last name to comply with this new ethics rule. I imagine my wife and kids will likely not be thrilled with the new last name of “Michigan Auto Law.”

But, more seriously, what’s the benefit here to consumers? Is there a real concern that consumers are being misled to think that Mr. Honigman and Mr Dykema are both alive and will be their lawyers?

I spoke above about laudable intentions and unintended consequences, and we have both at work here. I am close friends with Jules Olsman, the attorney who is largely responsible for this new amendment. Jules has been pushing for at least 10 years now for this new rule change. Jules, like myself and many other lawyers, has been alarmed with the explosion of illegal lawyer ambulance chasing and illegal solicitation of car accident victims in Michigan.

I believe this was the laudable aim of this new ethics rule. But there are much better ways to stop unethical attorney conduct in this state. It starts, by the way, with the agency that is tasked with regulating attorney conduct doing its job. The Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission has ignored the problem of attorney ambulance chasing for two decades even as the problem has exploded in cities like Detroit and as more and more lawyers have jumped on the bandwagon. Not one lawyer has been prosecuted, let alone disciplined, by the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission, even as thousands of car accident victims have been illegally solicited. This is inexcusable, and it is why many lawyers believe the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission is seriously broken.

But – the way to stop unethical and illegal attorney conduct in this state is not to make nearly every law firm in Michigan change their law firm building signs.

Additionally, another approach to unethical and illegal attorney conduct that misleads and deceives consumers of legal services would be to support – and possibly encourage the Michigan Supreme Court to enact – the State Bar of Michigan’s Proposed Ethics Advisory Opinion R-25.

The proposed ethics opinion, if enacted, would declare that:

A lawyer’s “participation in a for-profit online matching service that matches prospective clients with lawyers for a fee is not ethically permissible if the attorney’s fee is paid to and controlled by a non-lawyer and the cost for the online matching service is based on a percentage of the attorney’s fee paid for the legal services provided by the lawyer.”

But the consequences of our new legal advertising rule MRPC Rule 7.2(d) gets worse – saying goodbye to Google and Facebook.

Before we talk about how this rule almost certainly violates lawyers’ First Amendment Free Speech and Commercial Speech rights, let’s look at more unintended consequences. Most lawyers and law firms circulate branded clothing, or items like pens, flash drives, and other marketing objects. Since Rule 7.2(d) doesn’t define advertising, any law firm that engages in these common marketing giveaways must address Rule 7.2(d)’s requirements by including “the name, office address, and business telephone number of at least one lawyer responsible for the content of the advertisement.” A sweatshirt or a ballpoint pen that says “Skadden” (tradename for Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP), for example, would violate Rule 7.2(d) unless it includes all the required disclosures. That better be a very, very big pen from now on because that’s a lot of required disclosure information to fit on it.

Rule 7.2(d) effectively forces lawyers and law firms to retire nearly all of their existing marketing materials and to spend tens of thousands of dollars on new office signs for buildings. Yet there was no evidence introduced in the public record for ADM 2016-27 – the Supreme Court’s administrative file that generated the new legal advertising rule in MRPC 7.2(d) – that showed consumers would actually benefit from these new burdensome and expensive disclosures.

Assuming you even could fit in all of the information required by MRPC 7.2(d), how does including a law office address or a phone number of “at least one lawyer responsible for the content of the advertisement” in a Tweet, Facebook post, or an Instagram image protect legal services consumers?

And even if it did:

The Court could address these issues by excluding certain forms of advertising (like location markers, building signs or clothing) from the Michigan Rules of Professional Conduct’s definition of advertising. But even this approach doesn’t go far enough. As I said above, a far bigger problem exists.

The new rule violates attorneys’ First Amendment rights when applied to online advertisements and social media.

Internet and social media: How the new legal advertising rule violates the First Amendment

The biggest problem by far with the new legal advertising rule is that it violates the First Amendment by dictating the content of lawyers’ constitutionally protected commercial speech.

How?

Due to the burdensome, extensive disclosure requirements mandated by the new MRPC 7.2(d) – coupled with space limitations in Google ads on the Internet and ads on social media – the content of lawyers’ ads will be entirely consumed by and limited to what the Michigan Supreme Court has dictated that lawyers MUST say.

Let’s consider an example.

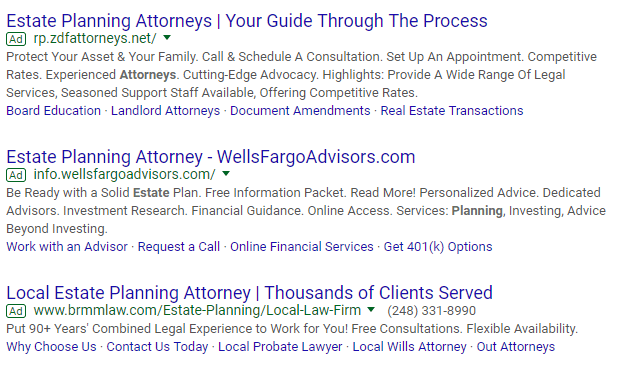

Search Google for estate planning attorneys, and you’ll get a page with two kinds of results: pay-per-click ads and organic search results. The pay-per-click ads appear at the top of the page, with the word “Ad” in a green text block:

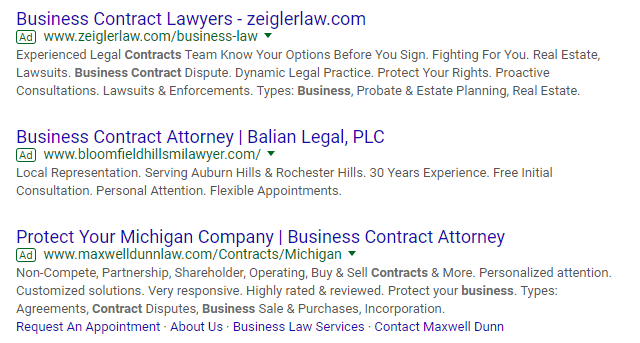

All kinds of attorneys use pay-per-click ads. You’ll find ads from business contract attorneys:

And immigration attorneys:

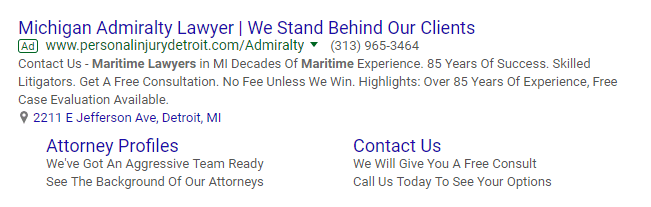

Even admiralty attorneys:

Lawyers participate in pay-per-click ads in dozens of different areas of law. With these pay-per-click ads, lawyers and law firms bid for the opportunity to appear at the top of the search results for particular keywords like divorce attorney or personal injury attorney. Google and other search engines charge these law firms when a consumer clicks one of their ads.

Importantly, especially in the context of applying MRPC 7.2(d)’s new legal advertising rules to Internet advertising, law firms choose the text of pay-per-click ads subject to character limits.

These character limits can change, but the current limit for Google is 110 characters.

Significantly, compliance with the new disclosure requirements of Rule 7.2(d) will require lawyers and law firms to now use up 97 of their available 110 characters with mandatory disclosure requirements, effectively killing the ability of lawyers to engage in pay-per-click advertising.

The text of a pay-per-click ad is critical for communicating with potential clients. Now this text will be replaced by the new disclosure requirements.

Law firms spend a great deal of time and energy determining exactly what to say with their limited 110 characters. Most law firms engage digital advertising agencies and marketing companies to track how effective these ads are. For many law firms that chose not to do television or yellow pages or big billboard signs, these ads are the lifeblood of their businesses.

The effect this will have on lawyers’ practices cannot be overstated. In my own area of law, car accidents and personal injury, we now have an ethics rule that puts all lawyers who DON’T advertise on television or on billboards at a very significant disadvantage to the lawyers who do.

Once these pay-per-click ads are subject to Rule 7.2(d), firms will have to comply with the new mandatory disclosures of Rule 7.2(d) and this leaves the law firm with only 13 characters to deliver a message to potential clients. This effectively eliminates a lawyer’s ability to engage in pay-per-click advertising on Google.

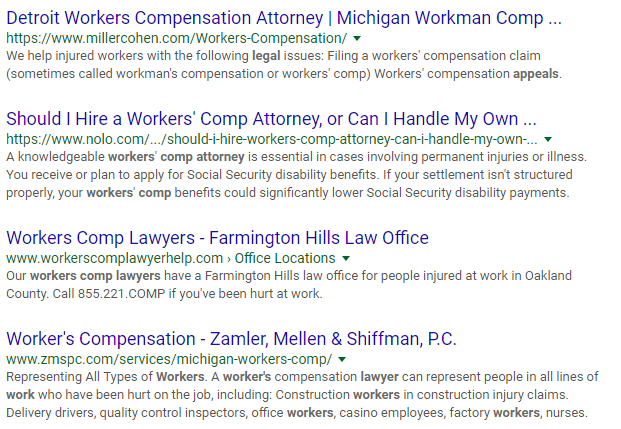

Similar limitations apply to organic Google results. In a Google search, organic results appear below pay-per-click ads. Organic results lack the Ad text block. For example, here are the initial organic results for worker’s comp attorneys:

Although these results aren’t pay-per-click ads, they function like ads. The text that appears under web addresses in organic results is called a meta-description—a text coded into each website. Like the descriptions in pay-per-click ads, law firms use meta-descriptions to get their messages across to potential clients and, hopefully, to attract consumers of legal services who are looking for a lawyer to hire.

Meta-descriptions are subject to character limits, just like pay-per-click ads. Platforms often revise their character limits, but the current limit for Google is around 160 characters. As a result, complying with Rule 7.2(d) severely restricts the number of characters available for law firms to communicate with prospective clients of legal services.

These concerns apply to ads in social media as well. Ads on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram are typically subject to character limits. Twitter limits advertisements to 256 characters. Facebook and Instagram allow up to 185 characters, depending on the ad format. Facebook’s rules currently require advertisers to use pictures for ads. But Facebook also limits text to 20% of a picture advertisement. Including all of the information required under Rule 7.2(d) would likely prompt Facebook to reject a law firm’s advertisements.

In effect, Rule 7.2(d) either eliminates or severely restricts commercial speech in the fastest growing area of advertising for legal services.

Professor’s opinion that new legal advertising rule doesn’t violate First Amendment failed to consider how lawyers use the Internet and social media

The only constitutional analysis available to the public when the Court adopted Rule 7.2(d) was the barely two-page April 2, 2018, e-mail from Wayne State University Law Professor Robert Sedler (submitted in ADM File No. 2016-27) who concluded that the new rule passed constitutional muster under the test from Central Hudson Gas & Electric v. Public Service Commission, 447 U.S. 557 (1980) because, in his view, it did not “interfere[] with the ability of [a] party to convey information to the public.”

But Professor Sedler’s conclusion can, at best, be true only for traditional 20th Century advertising like television ads, print media and billboards.

It’s clearly not true for most online ads.

The new MRPC requirements restrict so significantly the ability of attorneys to use Google and Facebook that these two critical platforms for online advertising are eliminated. Professor Sedler has a very good reputation, but I’m guessing he probably doesn’t do much pay-per-click advertising or spend much of his time crafting ads for legal services on social media.

The required disclosures under MRPC 7.2(d) limit the space available for attorneys’ commercial speech. In some cases, such as pay-per-click, these restrictions are so severe that they eliminate it as a means of commercial speech entirely.

Compliance with MRPC 7.2(d) with Google ads and with Facebook effectively silences attorneys. As a result, Rule 7.2(d) violates attorneys’ First Amendment rights.

Professor Sedler’s conclusion that MRPC 7.2(d) “does not interfere in any way with the ability of a lawyer or law firm to advertise that it provides legal services” is wrong. It not only interferes with it, it effectively kills the way tens of thousands of lawyers are using the internet to reach consumers in the 21st Century.

How MRPC 7.2’s legal advertising rule will fare under the Central Hudson test

Here’s how a federal court will apply the Central Hudson test to Rule 7.2(d) and online commercial speech. The Central Hudson test considers (1) “whether the expression is protected by the First Amendment”; (2) “whether the asserted governmental interest is substantial”; (3) “whether the regulation directly advances the governmental interest asserted; and (4) “whether it is not more extensive than is necessary to serve that interest.” (Central Hudson, 447 US at 566)

Regarding the first Central Hudson element, the First Amendment protects commercial speech when it “concern[s] lawful activity” and is “not … misleading.” (Central Hudson, 447 US at 556) As the United States Supreme Court put it in Ibanez v Florida Dep’t of Bus and Prof’l Reg, 512 US 136 (1994), “[O]nly false, deceptive, or misleading commercial speech may be banned.” (Ibanez, 512 U.S. at 142) In this case, MRPC 7.1 already prohibits false or misleading advertisements. So we can assume that MRPC 7.2(d) applies to speech that passes muster under the MRPC 7.1. And that means it applies to protected commercial speech.

Having satisfied the first Central Hudson prong, the next question is whether the asserted governmental interest is substantial. From comments submitted to the Court in ADM File 2016-27, it seems the goal of Rule 7.2(d) is to ensure that consumers can determine the attorney responsible for advertisements under phone numbers, web addresses, and trade names. Let’s assume for argument’s sake that this interest is “substantial” under Central Hudson and Ibanez.

The third question is whether Rule 7.2(d) “directly advances the governmental interest asserted.” (Central Hudson, 447 US at 566) The U.S. Supreme Court has made it clear that mere speculation or conjecture will not suffice for this prong, and that a state “must demonstrate that the harms it recites are real and that its restriction will in fact alleviate them to a material degree.” (Ibanez, 512 US at 143)

This empirical inquiry raises problems for Rule 7.2(d). No one cited evidence of consumer confusion at the May 2018 public hearing in ADM 2016-27. Those supporting Rule 7.2(d) relied largely on the kind of “speculation and conjecture” that the Ibanez court and other federal courts have rejected – “rote invocation[s] of the words ‘potentially misleading’” (Ibanez, 512 US at 146) and appeals to “common sense.” (Mason v Florida Bar, 208 F3d 952 (CA 11, 2000))

Moreover, there’s good reason to be skeptical of claims that Rule 7.2(d) is necessary to protect consumers. In 2015, the Association of Professional Responsibility Lawyers “surveyed all state lawyer regulation agencies regarding lawyer advertising complaints.” (Lynda C. Shely, From Bates to Blogging: 40 Years of Lawyer Advertising, 54-Dec Ariz. Att’y 30, 32 (2017)) Thirty-four jurisdictions responded, and “[t]he vast majority of [those] confirmed that virtually all the complaints they received about lawyer advertising were from other lawyers, not consumers.” (Emphasis in the original) The lack of empirical support for a connection between MRPC 7.2(d) and a state interest is reason enough to invalidate MRPC 7.2(d).

But the rule’s problems go even further when applied to online advertising and social media.

Rules that leave little or no room for attorneys’ commercial speech violate the First Amendment, as demonstrated by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling in Public Citizen Inc v Louisiana Attorney Discipline Board, 632 F3d 212, 228-229 (CA 5, 2011) (holding, among other things, that rule dictating font size and speed in disclaimers violated First Amendment because it “effectively ruled out” attorneys’ commercial speech).

Given character limits, Rule 7.2(d) – by dictating what attorneys MUST say in their ads – inhibits commercial speech when applied to much online advertising. Compliance with Rule 7.2(d) means that a firm placing a Google ad will have far fewer characters available for its message. And that means Rule 7.2(d) prevents attorneys from getting their full message to potential clients.

Rule 7.2(d)’s application to online advertisements is broader than necessary, contrary to Central Hudson, because any consumer who clicks on a law firm’s ad is taken to the law firm’s website. Firms typically include all of the Rule 7.2(d) information and much more on their websites. (There is no public evidence of a law-firm website that lacks the information at issue in Rule 7.2(d)). So Rule 7.2(d) curbs attorney speech in the name of consumer information when consumers can obtain all the necessary information with the click of a mouse. That fails Central Hudson.

For these reasons, Rule 7.2(d) violates the First Amendment when applied to online advertisements.

[NOTE: The above portions of this blog post are based in part on a letter to the Michigan Supreme Court regarding the amendment to Michigan Rule of Professional Conduct 7.2 (as enacted pursuant to ADM File No. 2016-27).]

Recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling shows why MRPC 7.2(d) runs afoul of 1st Amendment

In NIFLA v. Becerra (published on June 26, 2018), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a disclosure requirement for advertising because it was “unduly burdensome” on the 1st Amendment’s free speech guarantee as it applies to “commercial speech.” The Court observed that compliance with the disclosure requirement would result in the “statement from the government” “surround[ing]” the advertiser’s “statement” and “drown[ing] out the [advertiser’s] own message.”

Significantly, the same will be true with MRPC 7.2(d)’s disclosure requirements for legal advertising in Michigan.

For that reason – in addition to the compelling reasons outlined above – the new legal advertising rule in MRPC 7.2(d) is “unduly burdensome” on Michigan lawyers’ constitutionally protected “commercial speech.”

Notably, the “unduly burdensome” standard applied by the Supreme Court in NIFLA v. Becerra originates with the Court’s 1985 ruling in Zauderer v. Office of Disc. Counsel where the justices held the 1st Amendment’s free speech/commercial speech guarantee prohibits disclosure requirements in lawyer advertisements that are “unduly burdensome.”